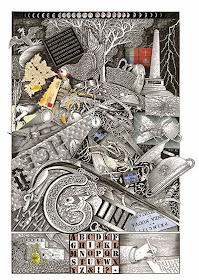

It is indeed. There are three illustrations, which all appear in the Studies chapter, where Shem, Shaun and Issy are having their lessons in the room above the Chapelizod pub.

|

| The Euclid diagram from page 293 |

Joyce to Frank Budgen, July 1939

(Letters, I,406)

In Greek mythology 'Gaia', the earth, was the great mother, and geometry means 'measuring the earth'. So Joyce's geometry lesson is all about revealing ALP, the great mother in Finnegans Wake. The Euclid diagram represents her pubic triangle, which Shem tricks Shaun into drawing. He says, 'I'll make you to see figuratleavely the whome of your eternal geomater.' 296.36. I'll make you see figuratively (plus fig leaf) the womb/home/who of your eternal mother (Gaia matêr: mother Earth plus geometry). The upper triangle represents ALP's apron, which the twins have lifted ('the maidsapron of our A.L.P.' 297.11). The lower triangle is her exposed 'muddy old triagonal delta' (297.24). Later it's called 'her bosky old delltangle' (465.03).

The image with two intersecting circles is called a Vesica Piscis (fish bladder), which was seen as a symbol of the womb in Eastern mysticism.

Here's Joyce's first sketch of it, from David Hayman's A First Draft Version of Finnegans Wake.

The two 'funny drawings' appear at the very end of the chapter, drawn by Issy as footnotes to a count of ten above. The ten, in a kind of deformed Irish, represent the chimes of the clock and the 10 Sephiroth of the Kabbala. See fweet to learn more.

Issy's drawn herself thumbing her nose, a gesture of ridicule, her final verdict on the quarrelling twins and the whole lesson. The gesture, with five fingers (including thumb) is inspired by the word 'Cush', standing for the number five in the count above. Elsewhere, Joyce gives us 'reechoable mirthpeals and general thumbtonosery' (253.28). 'The free of my hand to him!' is an offered slap.

I'd always imagined that these were drawn by Joyce. However, it turns out that they are a real girl's drawings, commissioned by James Joyce in Zurich!

The story is told by Fritz Senn:

'I think it was through Carola Giedion-Welcker that I once had a brief conversation with Hans von Curiel. He used to be the director of the Corso Theatre in Zurich, and Joyce may have paid him a tribute, at least Carola Giedion-Welcker told me so, in the Wake, where 'Hans the Curier' may figure as an avatar of Shaun the Post. What he told me, and it is worth passing on, is that Joyce called on him one night and requested a childish drawing to be put at the end of The Mime of Mick, Nick and the Maggies; it is the marginal illustration at the bottom of page 308 in Finnegans Wake. Joyce needed a genuine girl's drawing, and it was done by Hans von Curiel's daughter, significantly named Lucia.'

Joycean Murmoirs (2007). p48.

(The Mime of Mick, Nick and the Maggies is actually the chapter before the one with the drawings).

'Hans the Curier' can be found at 125.14

Joyce had already drawn his own version of these doodles, which is in

his first draft, reprinted in the James Joyce Archive volume (53.281).

He then got Lucia von Curiel to copy his pictures.

These drawings first appeared in the 1937 Corvinus Press book, Storiella as She is Syung, which also included an initial letter (left) by Lucia Joyce. So this lovely book opens and closes with a drawing by a Lucia.

This was the final edition of an extract from Work in Progress published before the book itself came out. Only 175 copies were printed, and they go for vast sums today.

Why did Joyce need a genuine girl's drawing? For the same reason that he largely assembled Finnegans Wake out of phrases taken from other writings, and also accepted coincidence as a collaborator. Joyce's book was a collective undertaking, in which he saw himself as a channel rather than the author.

'Every dimmed letter in it is a copy and not a few of the silbils and wholly words....The last word in stolentelling!' Finnegans Wake, 424.32

'Really it is not I who am writing this crazy book,' Joyce told a party of friends. 'It is you, and you,

and you, and that man over there, and that girl at the next table.'

Eugene Jolas, 'My Friend James Joyce' in James Joyce: Two Decades of Criticism (ed Givens), 1948

'The book was indeed his life and he believed that he was entrapping some part of the essence

of life within its pages....Joyce was not in his own opinion simply

writing a book, he was also performing a work of magic.'

J.S.Atherton, The Books at the Wake