|

| Clive Hart from flickr |

'Clive Hart, an Australian of a jovial and tolerant disposition, was, like myself trained in the sciences – physics in fact – and was also a major international authority on medieval kites and windsocks.'

Stevenson's blog sent me to a wonderful interview that Hart gave to Cabinet magazine in 2003, in which he discussed his fascination with early attempts at flight. Like everything Hart wrote, this is full of startlingly original ideas:

'People should have been thinking about bats [rather than birds]. But of course, bats were figures of evil. If they’d based their ideas a little bit more on bats, though, they might have gotten a bit further.....Because bats fly better and because the structure of bats’ wings is much easier to imitate.'

STRUCTURE AND MOTIF IN FINNEGANS WAKE

I've already written here about Clive Hart's role in the Great Kiswahili controversy of 1962-3, when he made a passionate defense of creative reading, against Jack Dalton's reductive intentionalism.

'Most modern critics will say, rightly or wrongly, that it doesn't matter a damn what any author intended, except in so far as that intention is borne out by the work itself. ''For all we know, JJ may have intended FW to be a cookery book. Who cares what he thought? What are the book's intentions?'''

Clive Hart to Roland McHugh, 1968, quoted in The Finnegans Wake Experience

But how do you find out a book's intentions? How do you find out what a book as odd as Finnegans Wake intends?!

Clive Hart came up with his own answer in Structure and Motif in Finnegans Wake, which he published in 1962, the same year that, with Fritz Senn, he launched the Wake Newslitter. You can read the whole book online in the James Joyce Scholars Collection here.

In 1962, nobody knew more about Finnegans Wake than Clive Hart. The following year, he would bring out A Concordance to Finnegans Wake, which combines a list of the 63,924 Wake words with a section called Overtones, listing 10,000 English words suggested by the Wake ones.

Hart was the first scholar to look at the way Joyce uses motifs – repeated rhythmic phrases – in the Wake. For Structure and Motif, he catalogued more than a thousand of them. Here's one example:

'Teems of times and happy returns. The same anew.' 215.22-3

'We drames our dreams tell Bappy returns. And Sein annews' 277.19

'-Booms of bombs and heavy rethudders?

-This aim to you!' 510.01-2

'Themes have thimes and habit reburns. To flame in you.' 614.08-9

For the reader, these motifs provide a reassuring element of familiarity in the confusion of the Wake. They are part of the musicality of the book.

These motifs are clearly 'intended' by the book, since everyone can recognize them.

The problem with Hart's book is when he dealt with Structure. He argued that the Wake is structured on several interlinked cycles, using various dream levels, Viconian cycles and the World-Ages of Indian philosophy (right).

As a student, in 1982, I went to the Joyce Centenary Symposium in Dublin, where I saw Hart take part in a panel discussion called Joyce the Masterbilker: The Architecture of Finnegans Wake. The panel also comprised Fritz Senn, David Hayman, Margot Norris, Luigi Schenoni, Nathan Halper, Melvin Seesholtz and Robert Boyle S.J. During the discussion, I was astonished to hear Hart say, 'There is no deep structure in Finnegans Wake.'

I was too in awe of the Joyceans to ask a question in Dublin. But later that year I saw Hart lecture at the University of London, where he repeated the statement that the Wake has no deep structure. At the end I asked him how, having written Structure and Motif in Finnegans Wake, he could say that. He said that he no longer believed in his own book!

'Clive Hart's Structure and Motif in Finnegans Wake took a much wider view, away from individual particles, and it was a big step forward. But I also know that Clive no longer believes in its results and would now throw about 95 per cent of it overboard.'

It strikes me that a creative reading of the Wake, like John Bishop's or John Gordon's, is an act of faith – faith that the patterns and meanings that the reader detects are objectively present in the book. Hart had lost this faith.

Jed Stephenson writes in his blog:

'After decades of work, even tentative answers to the questions of how the book was structured, or what its central themes were, were elusive. “The student of Finnegans Wake needs to be a humble person,” Clive wrote in the introduction to his concordance to the book. Those who claimed truly to understand it he viewed sceptically.'

He viewed those who claimed to understand the Wake sceptically because he understood them. When he wrote Structure and Motif, he had been one of them.

Jed Stephenson also quotes a comment that Hart made about the years he'd spent working on the Wake: 'What were we looking for? Were we looking for the wrong thing?'

A Topographical Guide to Ulysses

My favourite book of Hart's is A Topographical Guide to Ulysses, originally published by the Wake Newslitter Press in 1975. The first edition came out as a booklet, with a separate folder of maps by Leo Knuth. That summer in 1982, I wandered all over Dublin, exploring the city with those maps. For the 2004 centenary Bloomsday, Hart brought out a beautiful hardback edition, published by Thames and Hudson, with exquisite new maps by Ian Gunn.

The Guide demonstrates the extraordinary accuracy of the way in which Joyce, writing in far away Trieste, Zurich, and Paris, made his characters move around Dublin. Hart worked out how the novel operates in time and place using 1904 tram and train timetables, and by walking the streets of Dublin with a stopwatch. One of the big events of the 1982 symposium was 'O Rocks', a re-enactment of the Wandering Rocks episode by more than a 100 actors, based on Hart's own tabulation of the chapter. He himself played Father Conmee, who sets the chapter in motion. I followed Bloom around, with a radio pressed to my ear (listening to RTE's all-day dramatic reading of the whole novel).

Here's what Hart has to say about Bloom's route to the post office and baths in Lotuseaters:

'The simple, matter-of-fact style of the first few paragraphs of Lotuseaters conceals the remarkably tortuous character of Bloom's route...He is trying, of course, to reach the post office without being seen by acquaintances – especially perhaps, by Boylan, whose own advertising agency was evidently in the centre of town – and at the same time he is troubled by his own conscience and sense of personal failure. The meanderings which follow his initial apearance on the quay are like the aimless wanderings of a drugged and troubled man, Bloom's demeanour suggesting, indeed , that he may not be fully conscious of what he is doing....Thus far Bloom's wanderings describe the shape of a question mark.'

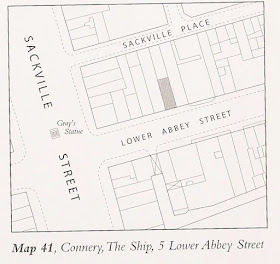

Here's another map, showing the Ship pub at 5 Lower Abbey Street, where Mulligan and Haines wait for Stephen to buy them drinks at noon. Stephen never arrives, sending a telegram instead.

Just four doors to the left of the Ship, at 1 Lower Abbey Street, stood Mooney's pub, now sadly gone, but still open when I visited Dublin. This is where Stephen goes drinking with the newspapermen at the end of the Aeolus episode:

I have money.

–Gentlemen, Stephen said. As the next motion on the agenda paper may I suggest that the house do now adjourn?

–You take my breath away. It is not perchance a French compliment? Mr O’Madden Burke asked. ’Tis the hour, methinks, when the winejug, metaphorically speaking, is most grateful in Ye ancient hostelry.

–That it be and hereby is resolutely resolved. All that are in favour say ay, Lenehan announced. The contrary no. I declare it carried. To which particular boosing shed? ... My casting vote is: Mooney’s!