|

I took this photo when visiting Sweny's in 2013

|

This is the beginning of South Leinster Street, Dublin. It's a terrace that forms the south wall of Trinity College, and is just over the road from Sweny the chemist. High up on the redbrick wall, you can see a ghost sign 'Finn's Hotel'.

|

Thom's Dublin Directory 1904

|

Nora Barnacle was working as a maid here in the summer of 1904, when she first met James Joyce and walked out with him to Ringsend, probably on 16 June.

Today, the Lincoln's Inn pub, down the road at 19 Lincoln Place, has a sign on its glass door: 'This was the original front door of Finn’s Hotel – Nora Barnacle worked here in June 1904.' The pub now offers Joyce's Stout ('don't worry, folks - this dry Irish

stout is far from being as complex as its name sake'), Bloomsday Lager

and Nora's Red Ale, all made by the Wilting Quill brewery of Lexington Kentucky.

Thom's Dublin Directory shows that 19 Lincoln Place was Michael Fanning's pub in 1904.

Even if this wasn't Finn's Hotel, it's nice to see it commemorated here.

'A STRANGE HOUSE': RETURN TO FINN'S HOTEL 1909

In 1909, Joyce returned to Dublin to open the first Irish cinema, the Volta Electric Theatre on Mary Street. He was accompanied by four Italian business partners, Nicolo Vidacovich, Antonio Machnich, Giuseppe Caris and Giovanni Rebez.

Joyce booked the Italians rooms in Finn's Hotel, probably because it was cheap and central. It also gave him the opportunity to visit the hotel and see the room where Nora had slept.

'Today I went to the hotel where she lived when I first met her. I halted in the dingy doorway before going in I was so excited. I have not told them my name but I have an impression that they know who I am. Tonight I was sitting at the table in the dining-room at the end of the hall with two Italians at dinner. I ate nothing. A pale-faced girl waited at table, perhaps her successor. The place is very Irish. I have lived so long abroad and in so many countries that I can feel at once the voice of Ireland in anything. The disorder of the table was Irish, the wonder on the faces also, the curious-looking eyes of the woman herself and her waitress....A strange land, a strange house, strange eyes and the shadow of a strange strange girl standing silently by the fire, or gazing out of the window across the misty College park. What mysterious beauty clothes every place where she has lived!'

To Nora, 19 November 1909, Selected Letters, p178

'The Four Italians have left Finn's Hotel and live now over the show. I paid about £20 to your late mistress, returning good for evil. Before I left the hotel I told the waitress who I was and asked her to let me see the room where you slept in. She took me upstairs and took me to it. You can imagine my excited appearnce and manner. I saw my love's room, her bed, the four little walls within which she dreamed of my eyes and voice, the little curtains she pulled aside in the morning to look out over the grey sky of Dublin, the poor modest silly little things on the walls over which her glance travelled while she undressed her fair young body at night.'

To Nora, 11 December 1909, Selected Letters, p187

In 1912, Nora visisted Ireland, and stayed in Finn's Hotel where 'in contrast to her husband's lachrymose visits to the shrine she experienced a small triumph at being guest instead of chambermaid.' (Ellmann, JJ, p323)

FINN'S HOTEL IN FINNEGANS WAKE

This is the cover of the Spring 1989 issue of A Finnegans Wake Circular, which contains 'The Name of the Book', a brilliant piece of detective work from Danis Rose and John O'Hanlon. You can download the whole run of the FWC from Ian Gunn's magnificent Joycetools page, set up in honour of Clive Hart.

Rose and O'Hanlon present conclusive evidence that Finnegans Wake was originally titled Finn's Hotel.

Joyce told his official biographer, Herbert Gorman, that he came up with the book's title at the very beginning of the project, in Nice in October 1922:

'Joyce, full to bursting with his new project, did not actually begin to put down notes and stray phases for the work until the autumn when he was enjoying the warm skies and Mediterranean sunsets at Nice. It is interesting to note that he had the title for the book in mind at this time and confided it to his wife. She a miracle among women, kept the title to herself for seventeen years although many a sly and curious friend attempted to trap her into revealing it.'

Herbert Gorman, James Joyce, 1941, p333

Sharing this secret with Nora would be a romantic gesture if the book was named after the hotel. Imagine her indifferent reaction to being told he was writing a book called Finnegans Wake!

Rose and O'Hanlon imagine the scene.

'When Joyce had thought of the book's title to be, he said to Nora: Nora, the name of this new book of mine - are you ready? - is Finn's Hotel. But this is to be strictly between the two of us. You are not to breathe a word of it to a sinner. Can you promise me that, a cuishla'

Rose and O'Hanlon's evidence for this comes from Joyce's notebooks, his letters to Harriet Shaw Weaver, and the text of Finnegans Wake itself.

In Joyce's notebook VI.B.25, written in Bognor Regis, in 1923, we first find the name of the hotel.

'Finn's Hotel.' VI.B.25, 81

'Finn's Hotel I House that Finn Built' VI.B.25.82

'Finn's Hotel I ... /they rifle wardrobes' VI.B.25. 82

In later notebooks from 1923-4, the name of the hotel appears several times, often as initials. F.H. can now become any public building.

'all tongues in F.H./ tower of babel' VI.B.6.102

'parl in FH' VI.B.2.42

'FH W[omen] talk from various stages (the centuries) children play in the courtyard. It becomes barracks, hospital, museum.' VI.B.2 2f

'Flying House (FH)' VI.B.2.94

'Kitty O'Shea=FH' VI.B.20.48

In February 1924, Joyce came up with a square sign, which he now used to stand for a public building instead of F.H. Here are some typical uses, from Roland McHugh's Sigla of Finnegans Wake.

The key evidence that the name of the hotel was also the book's title comes from Joyce's letter of 24 March 1924 to Harriet Shaw Weaver explaining his sigla system.

A GUESSING GAME WITH MISS WEAVER

According to Ellmann, when Joyce met Weaver in London in April 1927, he 'suggested

that she try to guess the title of the book.' (Ellmann 597). This was part of his campaign to involve her in his book, which she disapproved of.

Two notebook entries refer to a competition to guess the name of the house/title.

Jane Lidderdale and Mary Nicholson, HSW's biogaphers, and Ellmann describe the guessing game

that followed, selectively quoting the letters. They leave out some key evidence, in the mistaken

belief that the book's title was always Finnegans Wake.

|

HSW by Man Ray

|

16 April 1927. JJ: ‘I think I have done what I wanted to do. I am glad you like my punctuality as an engine driver. I have

taken this up because I am really one of the great engineers, if not the

greatest, in the world besides being a musicmaker, philosophist and

heaps of other things. All the engines I know are wrong. Simplicity. I

am making an engine with only one wheel. No spokes of course. The wheel

is a perfect square. You see what I am driving at, don’t you? I am

awfully solemn about it, mind you, so you must not think it is a silly

story about the mouse and the grapes. It’s a wheel, I tell the world.

And it’s all square.’

16 April 1927. HSW: 'A Wheeling Square...Squaring the Wheel.'

28 April 1927. JJ to HSW: 'What name or names would you give []?'

12 May 1927 JJ to HSW: 'I shall use some of your suggestions about [] of which you have a right idea. The

title is very simple and as commonplace as can be. It is not Kitty

O'Shea as some have suggested, though it is in two words. I want to

think over it more as I propose to make some experiments with it

also....My remarks about the engine were not meant as a hint at the

title. I meant that I wanted to take up several other arts and crafts

and teach everybody how to do everything properly, so as to be in the fashion.'

(This letter recalls Joyce's note 'Kitty O'Shea=FH' VI.B.20.4)

19 May 1927 HSW: 'One Squared'

31 May 1927 JJ: 'As

regards the title, ‘one squared’ can be used in the ‘math’ lesson by the

writer of Part II if he, or she, is so ‘dispoged’. The title I

projected is much more commonplace and accords with the J J & S and

A.G.S. & Co sign and it ought to be fairly plain from a reading of

w. The sign in this form means H.C.E. interred in the landscape.'

13 June 1927 HSW: 'Dublin Ale'

23 June 1927 JJ: 'Your guesses get nearer but [] is the name of a ‘place where’ not a ‘thing which’ or a ‘person who’.

28 June 1927 HSW: 'Ireland's Eye…Phoenix Park…Dublin Bay'

10

July 1927 JJ: Ireland's Eye (ey = island in Danish) is an islet off

Howth Head. Phoenix Park is rather close but it is a place not built by

hands — at least not all — whereas [] is.

26 July 1927 JJ: 'Two

of your guesses were fairly near the last is off the track. The piece I

am hammering at ought to reveal it.'

14

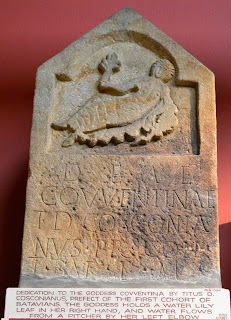

August 1927 JJ: 'As to 'Phoenix'. A viceroy who knew no Irish thought

this was the word the Dublin people used and put up a monument of a

phoenix in the park. The Irish was: fionn uisge (pron. finn ishghe

=clear water) from a well of bright water there'

N.D. August 1927 HSW: 'Finn MacCool'

30 August 1927 JJ: 'This

is to … tell you that the first word of your guess is right with an

apostrophe ‘s’ so I suppose you can finish it.'

17 September 1927. HSW: 'Finn's Town, Finn's City'.

The key letters are those of 23 June, 10 July and 30 August (the first and third previously unpublished). They reveal that the title of Joyce's book was in two words, 'a place', in Dublin, 'built by hands', whose first word was 'Finn's'. He did not reply to her final two guesses, which were very close.

The obvious solution is Finn's Hotel.

Here are Rose and O'Hanlon:

'Had Miss Weaver known in richer detail the minutiae of Joyce's early life, or had Joyce wished to continue the game, she would perhaps have finally guessed right, with unknown consequences for the title-page of the book that was published nearly twelve years later'

THE QUIZ CHAPTER

Joyce's

game with Harriet Shaw Weaver inspired question 3 in the Quiz chapter,

written in July-August 1927. Here Shem asks Shaun the title/ name of the house. On the manuscript, Joyce drew his square siglum next to

this question, showing that its subject was the title of his book.

3. Which title is the true-to-type motto-in-lieu for that Tick for Teac thatchment painted witt wheth one darkness, where asnake is under clover and birds aprowl are in the rookeries and a magda went to monkishouse and a riverpaard was spotted, which is not Whichcroft Whorort not Ousterholm Dreyschluss not Haraldsby, grocer, not Vatandcan, vintner, not Houseboat and Hive not Knox-atta-Belle not O’Faynix Coalprince not Wohn Squarr Roomyeck not Ebblawn Downes not Le Decer Mieux not Benjamin’s Lea not Tholomew’s Whaddingtun gnot Antwarp gnat Musca not Corry’s not Weir’s not the Arch not The Smug not The Dotch House not The Uval nothing Grand nothing Splendid (Grahot or Spletel) nayther Erat Est Erit noor Non michi sed luciphro?

Answer: Thine obesity, O civilian, hits the felicitude of our orb! 139.28-140.07

Shaun gets the answer wrong, mistakenly believing that he's been asked for the Dublin motto rather than a title. The introduction to the chapter alerts us to his mistaking a name for a motto:

'He misunderstruck and aim for am ollo of number three of them.' 126.08

Shaun couldn't have given a right answer without giving away the title of the book, which Joyce still wanted to keep secret in 1927, when the chapter was published in transition.

This question, with its list of wrong answers which are places,

businesses, pubs and hotels, only makes sense if the right answer is a place/business/pub/hotel. The correct answer to this question must be Finn's Hotel.

With 'Wohn Squarr Roomyeck' Joyce has included one of Miss Weaver's guesses, 'one squared', combined with his 1925-1931 Paris address, 2 Square Robiac. Other wrong answers are real places where the Joyces stayed, such as Antwerp.

'Antwerp I renamed Gnantwerp, for I was devoured there by mosquitoes.' To HSW 24.9.26.

'Grand nothing Splendid (Grahot or Spletel)'

Joyce stayed at the Grand Hotel in Antwerp from 17-20 September 1926, when he was bitten by the mosquitoes.

After retitling his book, Joyce could have rewritten the question, to include song titles ('which is not Miss Hooligan's Christmas Cake, not Enniscorthy, not Phil the Fluter's Ball...'). But he left his text as a palimpsest, revealing earlier versions of his plan.

The cover of Rose and O'Hanlon's article quotes page 514, where the title is concealed and revealed.

Finn's Hotel was a great title for Joyce's book, since it combines the name of a mythical Irish giant with a modern Dublin 'very Irish' hotel. It suits a book in which the last high king of Ireland appears as a publican, Tristan as a football hero, and Iseult as a film star flapper. Like the square siglum, it serves as a container, where any material could be placed.

WHEN DID JOYCE CHANGE THE TITLE?

The big mystery is when and why Joyce changed the title to Finnegans Wake. And how did Nora react when he told her that his book's title no longer commemorated their courtship?

When I posted this on twitter, Sam Slote shared an intriguing note made by Joyce in mid–late 1926.

'name K.O./ w of b of J’s f’s w / describe — f'. VI.B.15.99

Sam says, 'The 'w of b' is not clear, but J's f's w = Joyce's Finnegan's Wake (with apostrophe)'

Late 1926 was the very time that Joyce introduced the song into his book, in the opening chapter.

But if he was thinking of using Finnegan's Wake as a title in 1926, he had changed his mind by 1927, when he had his guessing game with Harriet Shaw Weaver and wrote the Quiz chapter.

Rose and O'Hanlon argue that the earliest dateable reference to the song as title is from 1937:

'It was in the Summer of [1937] at a time when he was revising the galleys of Part III, that we find the earliest (to date) datable - and yet not entirely undebatable - reference to Finnegans Wake qua title. On galley 199,17 just before ".i .. ' . . o .. l", Joyce added the phrase: "Name or redress him and we'll call it a night!", the second part of which he derived from page 2 of notebook VI.B.44 (which he was compiling around this time). The phrase appears to betoken a signal for a change of a name and/or of an address. (''Finn's Hotel", one should note, is both.) It may be, also, that he had (at least for a moment) intended to change the line that followed - ".i . .'s .o .. l" - for we find on page 45 of that same notebook (VI.B.44),18 after one misformulated and deleted attempt the cryptonym:

.i..e.a. ' .. a ..

That is "Finnegan's Wake", with its consonants and one vowel out, and the really curious thing about it is that it still retains the apostrophe. The final disapostrophised version can only have come later.'

Around the same time, in June 1937, Joyce had a long conversation about his book with Jan Parandowski.

''Perhaps you have heard that I am writing something...'

'Work in Progress.'

'Yes, it doesn't have a title yet. The few fragments which I have published have been enough to convince many critics that I have finally lost my mind, which by the way they have been predicting faithfully for many years.....

I saddened at the thought of the exhausting, obstinate toil that Joyce had put into his book, which had no other chance than to be regarded by both his contemporaries and posterity as a genial caprice....His last work seems to me a wrecked ship, incapable of delivering its cargo to anyone....

Such, more or less, was the burden of my silence, from which I could not rouse myself. Joyce was whistling thoughtfully some sort of tune that I did not recognize. I asked, 'What is that you are whistling?'

'Oh, it's one of those old, old ballads from the music hall; it ends: 'Isn't it the truth I've told you, /Lots of fun at Finnegan's wake.''

He repeated the last verse again. I didn't know at the time that it contained more or less the hidden source and the very title of his curious work. '

Jan Parandowski, 'Meeting with Joyce', in Portraits of the Artist in Exile (ed Willard Potts), pp 160-2

EUGENE JOLAS WINS 1,000 FRANCS

Around the same time, Joyce revived his title guessing game, offering a cash prize of 1,000 francs, which was a big sum in the late 30s. The final winner was Eugene Jolas, who later explained how he guessed the title:

'Some six months before Work in Progess was scheduled to apear, there was an amusing incident in connection with its title, then known only to Mr and Mrs Joyce. Often he had challenged his friends to guess it. We all tried: Stuart Gilbert, Herbert Gorman, Samuel Beckett, Paul Léon, and I, but we failed miserably. One summer night, while dining on the terrace of Fouquet's, Joyce repeated his offer. The Riesling was especilally good that night, and we were in high spirits. Mrs Joyce began to sing an Irish song about Mr Flannigan and Mrs Shannigan. Joyce looked startled and urged her to stop. This she did, but when he saw no harm had been done, he very distinctly, as a singer does it, made the lip motions which seemed to indicate F and W. My wife's guess was Fairy's Wake. Joyce looked astonished and said 'Brava! But something is missing.' For a few days we mulled over it. One morning I knew it was Finnegans Wake, although it was only an intuition. That evening I suddenly threw all the words into the air. Joyce blanched. Slowly he set down the wineglass he held. 'Ah, Jolas, you've taken something out of me,' he said, almost sadly. When we parted that night, he embraced me, danced a few of his intricate steps, and asked: 'How would you like to have the money?' I replied: 'In sous'. The following morning, during my absence from home, he arrived with a bag filled with ten-franc pieces. He gave them to my daughters with instructions to serve them to me at lunch. So it was Finnegans Wake. All those present were sternly enjoined not to reveal it, and we kept it a secret until he made the official announcement at his birthday dinner on the following February second.'

Eugene Jolas, 'My Friend James Joyce', in Givens (ed) James Joyce: Two Decades of Criticism, Vanguard, 1948.

Oh to time travel back to the terrace of Fouquet's on that summer night in 1938. I would walk up to Joyce's table and say, 'The title is Finn's Hotel!' What would he have said? How would Nora have reacted?

Harriet Shaw Weaver, who was the source of the money for the cash prize, only found out the name of the book when she saw the proofs for the title page on 4 February 1939.

|

| A pint of Joyce's stout at the Lincoln's Inn, June 2022 |