'Mr Joyce has been looking at FINNEGANS WAKE several times lately and every time he finds some misprints. In view of the possible necessity of a second edition of the book I think it will be well to start making the corrections right away....He says to me that he is sure the misprints must have crept in after his reading of the first proofs as he did not pass a single letter. '

Paul Léon to Richard de la Mere of Faber, 22 July 1939, from the Joyce Digital Archive

In April 1940, nine months after Finnegans Wake was published, George Pelorson asked James Joyce, 'What are you going to do? Are you writing?' 'No, I'm rereading and revising Finnegans Wake.' 'Why?' 'Well, I'm adding commas.'

He wasn't joking.

These are just a few of Joyce's c800 revisions, published as a sixteen-page pamphlet by Viking press in 1945, which you can read online here, on Eric Rosenbloom's excellent Wake website rosenlake.net. Thanks to Peter Parker who scanned the booklet.

Joyce could have said, 'I'm adding exclamation marks'. He added 14 to Anna Livia's final monologue.

This looks like it might have changed the tone of the ending, but it already had lots of exclamation marks (on p625, where he added three, there had been six previously).

The corrections weren't incorporated in the Viking Press text until 1958. Until then, readers who got this pamphlet could go through their copies of Finnegans Wake adding all these commas and exclamation marks themselves! Did anybody ever do that?

In 2018, Sam Slote had a geat article in the James Joyce Quarterly discussing the convoluted history of these corrections, which were applied differently by Faber in the UK and Viking in the USA.

The published list of corrections itself has misprints, which were only fixed by Faber in 1975.

The bulk of Sam's article is an annotated list of the corrections themselves, including the 'corrections to the corrections.'

When I shared this on facebook, Sam commented, 'It's probably the geekiest thing I've ever written (and that's saying something). Unfortunately I found a few mistakes *after* it was published.'

The application of the corrections explains a few strange features of some of the editions. Rather than reset the whole page, the printers squeezed the new commas into existing spaces.

I asked Sam if Joyce had been told he could only make tiny corrections. Sam replied, 'Yes; he had limited latitude with the corrections; as indeed was also the case with the revisions made on the galley- and page-proofs. Unlike Shakespeare and Co., he was dealing with a real publisher.'

This must have taken a lot of self-control on Joyce's part! His earlier habit with proofs was not to correct misprints but to add loads of new material. Here's a typical page from the third set of proofs of the Jaun episode given to transition, in May 1928.

Joyce couldn't get away with this sort of behaviour with Faber and Faber and Viking.

Even so, old habits die hard. He couldn't resist adding a bit of new text to page 176, even though it meant cutting a pantomime reference to Ali Baba.

Sam commented, 'That's one of the few emendations that affects more than one line. This particular one throws off the lineation for nine lines!!'

When I asked Sam for his permission to quote him here, he wrote, 'Yes, please do. And this gives me a chance to correct a big mistake: in order to correct the misalignment of the marginalia in II.2, Faber used the Viking plates for the 75. However, for some weird reason, five pages in II.2 still used the old Faber plates, which is evident since the font size of the marginalia is noticeably smaller. The affected pages are: 275, 281, 285, 297, 301.'

Finn Fordham has also made a detailed study, in which he worked out that 28% of the corrections were added commas. He also comments on this one.

Finn describes this added question mark as 'a rare insertion of an editor’s voice or presence, as if detached from the text at hand, an aside to the reader which, like us, asks ‘what exactly is all this?’

On facebook, Finn shared his own favourites: 'My deep geek favourites are on pages 285 and 287: for ''redor' read 'erdor'... for 'erdor' read 'odrer'. Both gratuitous anagrams (i.e. re-orderings) of "order". Which is what they were when first entered onto early draft levels: 'cyclic order... violated' and 'applepine order'. "Considerations of space influenced [his] lordship's decisions".'

Changing 'redor' to 'erdor' at 285.01 gives us HCE's initials. is this a rare example of a genuine correction to a misprint?

In his introduction to the Alma Classics Finnegans Wake, Sam Slote says that only one of Joyce's corrections 'really helps.' Here it is:

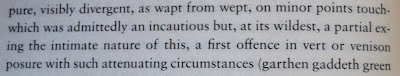

In this description of HCE's sin in the park, two lines have been swapped, wrecking not just the syntax but two words, 'touching' and 'exposure'.

As corrected by Joyce, sense and words are restored.

But here's one added comma which sabotages the text

The first edition had this.

We can read this as the hydromine used the Sowan and Belting system. Joyce's added comma maroons the word 'system' and makes no sense:

In fact there is a genuine misprint in this line, which Joyce missed – he originally wrote 'Beltiny'.

FULL STOPS

My favourite

punctuation change is a full stop, added at 257.27 after the word 'the'.

Here 'the.' is followed by a hundred-letter thunderword made up of different ways of saying 'shut the door'.

Finnegans Wake never ends – its last word is 'the' without a stop. Luca Crispi discovered that after writing that final 'the', Joyce added full stops after definite articles in places where doors are being closed.

'who oped it closet thereof the. Dor' (FW 020.17-18).

'that henchwench what hopped it dunneth there duft the. Duras' (334.29).

He missed one door being locked where he could have added a stop.

'bolt the thor.' 279. F 19

Dirk Van Hulle describes the significance of the stop on p257:

'In the Wake the full stop is never used only to mark an end but to indicate the possibility of a new sentence. Although this extra full stop is camouflaged and disguised as one of the 'Corrections of Misprints'' on the errata lists, it is not just an accidental but one of the most subtle constantive variants in modern literature, Giordano Bruno's coincidentia oppositorum summarized in the smallest of textual marks. It is significant that this change was made after the work was 'finished' and presented to the public, emphasizing the fact that even as Wake the work continued to be in progress: a full stop indicating the unfinishedness of a sentence, as a textual counterpint to the full-stopless closing of the book.'

Dirk Van Hulle, 'The Lost Word', in How Joyce Wrote Finnegans Wake, p 454-5

Joyce sometimes uses punctuation marks as pictures. In the Phoenix Park Nocturne, where the park animals and birds are settling down for the night, we read 'the birds, tommelise too, quail silent. ii.'

Joyce gave Jacques Mercanton an extraordinary note on this: ‘two little birds, male and female, release their little prayers, the two dots on the i's.’

If there are fans of wild punctuation out there, I recommend page 124. This is a discussion of punctuation as puncture marks - paper wounds - in the letter pecked by a hen out of a dunghill.

Joyce didn't suggest any corrections for this passage! Even so, according to Rose and O'Hanlon, it includes several misprints. Here's their corrected text version.

Thinking about pictorial punctuation reminded me of the stop at the end of the 'Ithaca' chapter of Ulysses. The answer to the final question, this marks the moment that Bloom falls asleep. The stop here is being used as a picture of his conscious mind shutting down, like an old tv screen image collapsing to a white dot.

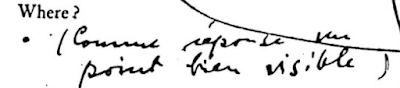

Joyce told the French printer of the first edition that he wanted 'un point bien visible.'

The printer gave him a black square (a quadrilateral six point typesetters 'em).

Joyce's symbol for Finnegans Wake was also a square.

'I am making an engine with only one wheel. No spokes of course. The wheel is a perfect square. You see what I'm driving at don't you? I am awfully solemn about it, mind you, so you must not think it is a silly story about the mouse and grapes. No, it's a wheel, I tell the world. And it's all square.'

To Harriet Shaw Weaver, 12 May 1927

So a black square is a perfect image and symbol of Joyce's 'lingerous longerous book of the dark' (251.23). I like to look at this little black square in Ulysses through a magnifying glass and think of it as a portal into Finnegans Wake. Could it be a microdot containing the whole of Joyce's book?

Postscript from twitter

This is an annotation by Clive Driver, from his James Joyce's Ulysses: The Manuscript and First Printings Compared, 1975.

It looks to me like a drawing of James Joyce's spectacles, which magnified his left 'good' eye - the eye he used to finish Finnegans Wake with.

'Retinal congestion suddenly developed in my left (the one really left) eye in consequence of months of day and (literally) allnight work in finishing WiP....but it was only strain and righted itself with a few weeks rest.'

To Pound, 9 February 1938, Letters III, 415

Dirk Van Hulle describes the significance of the stop on p257:

'In the Wake the full stop is never used only to mark an end but to indicate the possibility of a new sentence. Although this extra full stop is camouflaged and disguised as one of the 'Corrections of Misprints'' on the errata lists, it is not just an accidental but one of the most subtle constantive variants in modern literature, Giordano Bruno's coincidentia oppositorum summarized in the smallest of textual marks. It is significant that this change was made after the work was 'finished' and presented to the public, emphasizing the fact that even as Wake the work continued to be in progress: a full stop indicating the unfinishedness of a sentence, as a textual counterpint to the full-stopless closing of the book.'

Dirk Van Hulle, 'The Lost Word', in How Joyce Wrote Finnegans Wake, p 454-5

Joyce sometimes uses punctuation marks as pictures. In the Phoenix Park Nocturne, where the park animals and birds are settling down for the night, we read 'the birds, tommelise too, quail silent. ii.'

Joyce gave Jacques Mercanton an extraordinary note on this: ‘two little birds, male and female, release their little prayers, the two dots on the i's.’

If there are fans of wild punctuation out there, I recommend page 124. This is a discussion of punctuation as puncture marks - paper wounds - in the letter pecked by a hen out of a dunghill.

Joyce didn't suggest any corrections for this passage! Even so, according to Rose and O'Hanlon, it includes several misprints. Here's their corrected text version.

Thinking about pictorial punctuation reminded me of the stop at the end of the 'Ithaca' chapter of Ulysses. The answer to the final question, this marks the moment that Bloom falls asleep. The stop here is being used as a picture of his conscious mind shutting down, like an old tv screen image collapsing to a white dot.

Joyce told the French printer of the first edition that he wanted 'un point bien visible.'

|

| posted by Sam Slote on twitter |

The printer gave him a black square (a quadrilateral six point typesetters 'em).

Joyce's symbol for Finnegans Wake was also a square.

'I am making an engine with only one wheel. No spokes of course. The wheel is a perfect square. You see what I'm driving at don't you? I am awfully solemn about it, mind you, so you must not think it is a silly story about the mouse and grapes. No, it's a wheel, I tell the world. And it's all square.'

To Harriet Shaw Weaver, 12 May 1927

So a black square is a perfect image and symbol of Joyce's 'lingerous longerous book of the dark' (251.23). I like to look at this little black square in Ulysses through a magnifying glass and think of it as a portal into Finnegans Wake. Could it be a microdot containing the whole of Joyce's book?

Postscript from twitter

This is an annotation by Clive Driver, from his James Joyce's Ulysses: The Manuscript and First Printings Compared, 1975.

It looks to me like a drawing of James Joyce's spectacles, which magnified his left 'good' eye - the eye he used to finish Finnegans Wake with.

'Retinal congestion suddenly developed in my left (the one really left) eye in consequence of months of day and (literally) allnight work in finishing WiP....but it was only strain and righted itself with a few weeks rest.'

To Pound, 9 February 1938, Letters III, 415

|

| Photograph by Lipnitski |

Lovely.

ReplyDeleteDid the O'Hanlon brothers ever publish that hypertext version they promised? It's been over a decade now...

Thanks. They've published all the drafts of Finnegans Wake in the James Joyce Digital Archive, which is a wonderful resource. They include an isotext for each chapter ('an electronic hypertext databank specifying, differentiating and layering all authorial/non-authorial (scribal), documented/undocumented, valid, suspect or corrupting textual operations.' You can read the drafts and make your own editorial decisions. http://www.jjda.ie/main/JJDA/JJDAhome.htm

Delete