|

| The Liffey by Edward Smyth, 1787, on the Custom House |

In November 1938, sixteen years after he began Finnegans Wake by the seaside in Nice, James Joyce wrote its final pages. Anna Livia Plurabelle, the Liffey, dies as she flows into Dublin bay and merges with her father, the sea.

'I am passing out. O bitter ending! I'll slip away before they're up. They'll never see. Nor know. Nor miss me. And it's old and old it's sad and old it's sad and weary I go back to you, my cold father, my cold mad father, my cold mad feary father, till the near sight of the mere size of him, the moyles and moyles of it, moananoaning, makes me seasilt saltsick and I rush, my only, into your arms. I see them rising! Save me from those therrble prongs! Two more. Onetwo moremens more. So. Avelaval. My leaves have drifted from me. All. But one clings still. I’ll bear it on me. To remind me of. Lff! So soft this morning, ours. Yes. Carry me along, taddy, like you done through the toy fair! If I seen him bearing down on me now under whitespread wings like he’d come from Arkangels, I sink I’d die down over his feet, humbly dumbly, only to washup. Yes, tid. There’s where. First. We pass through grass behush the bush to. Whish! A gull. Gulls. Far calls. Coming, far! End here. Us then. Finn, again! Take. Bussoftlhee, mememormee! Till thousendsthee. Lps. The keys to. Given! A way a lone a lost a last a loved a long the'. 627.34-628.16

Read this aloud (preferably in a Dublin accent) to get the rhythm, repeated rhymes, the cries of the gulls and the 'whsh!' sounds of the sea. Here's a video from chilloutvibe to inspire you.

'I am passing out'

The final chapter is about passing from the book's night world to waking reality.

This is the bitterness of the salty sea and Anna's bitter disillusion with HCE/Dublin. As she moves away from the city, he/it shrinks in comparison with the vast sea.

'I thought you the great in all things, in guilt and in glory. You're but a puny.' 627.23

There's a precurser of this on page 261, in a passage written in 1934-5:

'They are coming, waves. The whitemaned seahorses, champing, brightwindbridled, the steeds of Mananaan'

'Flow over them with your waves and with your waters,

'But such a tide as moving seems asleep,

Too full for sound and foam,

When that which drew from out the boundless deep

Turns again home.'

'For all the bold and bad and bleary they are blamed, the seahags.' 627.25

Silent, oh Moyle! be the roar of thy water,

Break not, ye breezes, your chain of repose

'They'll never see. Nor know. Nor miss me. And it's old and old it's sad and old and weary...'

Here she moves from short choppy sentences to one very long one, as if she's just been swept up by the first big wave.

There's a precurser of this on page 261, in a passage written in 1934-5:

'Hencetaking tides we haply return, trumpeted by prawns and ensigned with seakale, to befinding oneself when old is said in one and maker mates with made (oh my!)'

According to the Digital Archive, in the 1934 typescript, Joyce wrote 'when old it's sad'. Could this phrase have inspired the book's ending?

COLD MAD FEARY FATHER

'it's sad and old and weary I go back to you, my cold father, my cold mad father, my cold mad feary father, till the near sight of the mere size of him, the moyles and moyles of it, moananoaning....'

|

| Oceanus, a mosaic from the Zeugma Museum, Turkey |

The cold mad father is the Greek and Roman god Oceanus, Poseidon/Neptune or the Irish sea god Manannan MacLir - suggested in 'moananoaning'.

'They are coming, waves. The whitemaned seahorses, champing, brightwindbridled, the steeds of Mananaan'

Proteus

'Flow over them with your waves and with your waters,

Mananaan, Mananaan MacLir...'

Scylla and Charybdis

Above Stephen quotes a chant from George Russell's play 1907 Deirdre, in which Russell himself played the sea god.

Above Stephen quotes a chant from George Russell's play 1907 Deirdre, in which Russell himself played the sea god.

'moananoaning' reminds me of the keening of female mourners at an Irish wake or graveside - a tradition going back thousands of years.

Edmund Lloyd Epstein in A Guide through Finnegans Wake finds echoes of Tennyson's 'Crossing the Bar' in Anna's monologue. He traces 'moananoaning' and 'far calls' (628.13) to the first verse:

'Sunset and evening star,

And one clear call for me!

And may there be no moaning of the bar,

When I put out to sea.'

'Moaning of the bar' refers to the sound made by waves crashing on a sandbar, at a river mouth or harbour entrance, when the tide is low. In the poem, Tennyson asks for a high tide 'too full for sound and foam' and a smooth sea - an easy death. 'May there be no moaning' sounds like 'May there be no mourning'.

x

Too full for sound and foam,

When that which drew from out the boundless deep

Turns again home.'

Here Epstein finds echoes in 'you're turning' 627.02 and 'Home!' 627.24

Epstein says that this verse 'describes exactly the pilgrimage of Anna Livia; she once came out of her great father the Sea, and now she is turning again for home.'

'old it's sad and weary' and 'cold mad feary' derive from 'bold and bad and bleary' on the previous page:

'moyles and moyles of it'

'miles and miles' said in a Dublin accent.

The Sea of Moyle is the north channel of the Irish Sea, between Antrim and Scotland, which appears in a song by Thomas Moore.

Break not, ye breezes, your chain of repose

Joyce described this in a letter to Giorgio as 'that part of the Irish Sea which is now called St George's Channel.' (LIII 339)

'And its old and old it's weary I go back to you,

my cold father,

mother,

and old it's sad & weary mother

I go back to you,

my cold father

my cold mad father

My cold mad bleary father,

till the sight of him makes me saltsick

and I rush into your arms'

'-- God, he said quietly. Isn't the sea what Algy calls it: a great sweet mother? The snotgreen sea. The scrotumtightening sea. Epi oinopa ponton. Ah, Dedalus, the Greeks. I must teach you. You must read them in the original. Thalatta! Thalatta! She is our great sweet mother. Come and look.

Stephen stood up and went over to the parapet. Leaning on it he looked down on the water and on the mailboat clearing the harbour mouth of Kingstown.

-- Our mighty mother, Buck Mulligan said.'

'I will go back to the great sweet mother,

'I will go back to the great sweet mother,

'Swinburne's central emotional drive was the need to worship and achieve an ecstatic loss of self. As a boy he expressed this drive through encounters with the sea.'

Joyce's sea is not sweet but bitter and cold as death. It makes Anna 'seasalt saltsick', like the 'bowl of bitter waters' that Stephen sees when he looks at the sea and thinks of his own mother's death.

'he saw the sea hailed as a great sweet mother by the well-fed voice beside him. The ring of bay and skyline held a dull green mass of liquid. A bowl of white china had stood beside her deathbed holding the green sluggish bile which she had torn up from her rotting liver by fits of loud groaning vomiting.'

The arms are rising waves, the prongs of Neptune's trident (triple prongs) and Dublin's Bull Wall and South Wall which stick out into the sea.

This line is based on a memory of Maria Jolas, which she describes in the wonderful opening of A Woman of Action – A Memoir and Other Writings (2004).

''Carry me along, taddy, like you done through the toy fair!' The words are James Joyce's but the experience was mine, drawn from the well of distant recall in the course of a dinner-table discussion: how far back can memory reach?

Maria Jolas A Woman of Action – A Memoir and Other Writings (2004) p 9

All our fathers are included too, since Finnegans Wake is, as J.S Atherton wrote, 'everyone’s dream, the dream of all the living and the dead'.

'You know, the Carry me along, taddy is nothing like the opening of Portrait and yet when I read the end of FW I keep hearing Portrait in this line. Is that just my crazyness?'

Dominique (Cachou Le Pitou) answered:

'No Karl, not crazy, it's baby tuckoo, the moocow, and the Mississippi Hare coming for to carry us home.'

'The stage manager called out: ‘What will I do with this act, Mr. Ziegfeld?’ ‘Wash up him and the bird,’ said Flo [Ziegfeld] and that was the last of the Italian and his trained canary... Hype Igoe, the World's sporting writer, heard of the incident..and in commenting..upon Frank Moran, heavy weight pugilist, advised that matchmakers ‘wash him up’. The phrase caught the sporting fancy..and has become a colloquial fixture..as a meaty synonym for finals and farewell.'

Balfe's 'Then You'll Remember Me' from The Bohemian Girl starts with 'other lips'.

'With drooping wings ye cupids come,

and scatter roses on her tomb,

soft and gentle as her heart;

Keep here your watch, and never part'

'in this scherzarade of one’s thousand one nightinesses' 51.04

'And into the river that had been a stream (for a thousand of tears had gone eon her and come on her...' 159.10

'We’ve heard it sinse sung thousandtimes.' 338.01

'one thousand and one other blessings will now concloose thoose epoostles' 617.04

'A hundred cares, a tithe of troubles and is there one who understands me? One in a thousand of years of the nights?' 627.14

'Lps' are lips, and the keys are also a kiss - the key in a kiss given by Arrah Na-Pogue (Arrah of the kiss) in Boucicault's play.

'in the good old bygone days of Dion Boucicault, the elder, in Arrah-na-pogue, in the otherworld of the passing of the key of Two-tongue Common' 385.02

'If it’s me chews to swallow all you saidn’t you can eat my words for it as sure as there’s a key in my kiss.' 279.F06

'How you said you'd give me the keys of my heart. Only now it's me who's got to give...The keys to. Given!'

In The Sleeping Beauty, the heroine is awakened by a kiss, referred to a few pages earlier in Anna's letter:

'That was the prick of the spindle to me that gave me the keys to dreamland.' 614.28

'In Ulysses, to depict the babbling of a woman going to sleep, I had sought to end with the least forceful word I could possibly find. I had found the word 'yes', which is barely pronounced, which denotes acquiescence, self-abandon, relaxation, the end of all resistance. In Work in Progress, I've tried to do better if I could. This time, I have found the word which is most slippery, the least accented, the weakest word in English, a word which is not even a word, which is scarcely sounded between the teeth, a breath, a nothing, the article the.'

Louis Gillet, Stèle pour James Joyce, Marseille 1941, pp.164-65

And here's Ulysses.

Writing after his friend's death in 1941, Frank Budgen compared the ending with 'The Dead':

'The key of Ulysses is too bright, its movement too rapid for that pity and reconciliation which provide the magical end of the story, 'The Dead', to have any part in it, but that same human element expressed with yet greater artistry does return in the last pages of Finnegans Wake when Anna Livia goes forth by day, as a woman (wife and mother, representative of all flesh) to join the countless generations of the dead, as a river to become one with the god, her father Ocean....The last work of Joyce ends, as did his first, in the contemplation of the mystery of death. In both cases the rebellious pity of the human heart finds in the beauty of a constant element of nature — in the one falling snow, in the other smooth gliding water — the symbol and the instrument of reconciliation with human destiny. We had hoped for further years and other labours. We cannot imagine a fitter swan song.'

'This postscript had probably been carried in its completed form for many years in the prodigious brain that engendered it. The first version, which was only about two a half pages long, was written in one afternoon, in December 1938. It was a veritable deliverance. Joyce brought it with him when we met that evening for his usual half-past eight rendez-vous in Madame Lapeyre's pleasant bistrot, on the corner of the Rue de Grenelle and the Rue de Bourgogne...'

'In Memory of Joyce', Poésie No V (1942), reprinted in James Joyce Volume 2: The Critical Heritage, (ed Robert Deming)

'My daughter-in-law staged a marvellous banquet for my last birthday and read the closing pages on the passing-out of Anna Livia — to a seemingly much affected audience. Alas, if you ever read them you will see they were unconsciously prophetical!'

To Constantine Curran, 11 February 1940, Letters, p 408

For a lovely creative reading of the final monologue, see Orlando Mezzabotta's 'ALP's reGrettas or HCE's Dämnerung' which is online here.

The sea is more usually called a mother and, in his first draft, Joyce included both parents:

my cold father,

mother,

and old it's sad & weary mother

I go back to you,

my cold father

my cold mad father

My cold mad bleary father,

till the sight of him makes me saltsick

and I rush into your arms'

Stephen stood up and went over to the parapet. Leaning on it he looked down on the water and on the mailboat clearing the harbour mouth of Kingstown.

-- Our mighty mother, Buck Mulligan said.'

Mulligan is quoting Swinburne's 'The Triumph of Time', which is the source of Anna's 'I go back to you':

'I will go back to the great sweet mother,

'I will go back to the great sweet mother, Mother and lover of men, the sea.

I will go down to her, I and none other,

Close with her, kiss her and mix her with me;Cling to her, strive with her, hold her fast:

O fair white mother, in days long past

Born without sister, born without brother,

Set free my soul as thy soul is free.''The Triumph of Time'

'Swinburne's central emotional drive was the need to worship and achieve an ecstatic loss of self. As a boy he expressed this drive through encounters with the sea.'

Rikky Rooksby, Swinburne: A Poet's Life, Routledge, 1997

Elsewhere Joyce turns Swinburne into 'Swimbourne':

cf 'slept the sleep of the swimbourne in the one sweet undulant mother of tumblerbunks' 41.06

Joyce's sea is not sweet but bitter and cold as death. It makes Anna 'seasalt saltsick', like the 'bowl of bitter waters' that Stephen sees when he looks at the sea and thinks of his own mother's death.

'It lay behind him, a bowl of bitter waters. Fergus' song: I sang it alone in the house, holding down the long dark chords. Her door was open: she wanted to hear my music. Silent with awe and pity I went to her bedside. She was crying in her wretched bed. For those words, Stephen: love's bitter mystery.'

Telemachus

PRONGS OF THE SEA

'I rush, my only, into your arms. I see them rising! Save me from those therrble prongs! Two more. Onetwo moremens more. '

The arms are rising waves, the prongs of Neptune's trident (triple prongs) and Dublin's Bull Wall and South Wall which stick out into the sea.

'Moremens' are mermen and 'An Mhuir Mheann', the limpid sea, another name for the Irish Sea.

The first words of the monologue are 'Soft morning, city!' 619.20

'It is the softest morning that ever I can ever remember me' 621.08

'Softly so.' 624.21

Avelaval.

'Ave atque vale' - Hail and farewell, from Catullus' elegy on his dead brother.

Paul Devine tells me that 'Hail and Farewell, Ave, Salve, Vale, from George Moore has also been cited as a possible source.'

'L'aval' is 'downstream' in French. Fweet suggests the Hebrew 'havel havalim': vanity of vanities in Ecclesiastes.

'My leaves have drifted from me. All. But one clings still. I’ll bear it on me. To remind me of. Lff!'

The flowing Liffey has been carrying autumn leaves, which are also the pages of the book that fall away as we read the final monologue:

'Soft morning, city! Lsp! I am leafy speafing. Lpf!....Only a leaf, just a leaf and then leaves....I am Leafy, your goolden...' 619.

Only one leaf is left - the final page. She carries it to remind her of life.

'So soft this morning ours.'

'It is the softest morning that ever I can ever remember me' 621.08

'Softly so.' 624.21

There's a shift of perspective from carrying to being carried. As she hits the wide sea, she reverts to childhood, and is now herself being carried by her cold mad feary father - the sea. This brings back a childhood memory of being carried through a toy fair.

'Carry me along, taddy, like you done through the toy fair!'

''Carry me along, taddy, like you done through the toy fair!' The words are James Joyce's but the experience was mine, drawn from the well of distant recall in the course of a dinner-table discussion: how far back can memory reach?

It was night, we were

walking along the acetylene lighted dusty 'midway' of the Jefferson

County Fair, on the outskirts of Louisville Kentucky. I was perched on

my tall young father's broad shoulders, my legs dangling onto his chest,

hands clasping his head. Was mother with us? Were there two older

children walking beside us? Was there a younger sister or a new baby at

home? Perhaps, indeed, probably, but I have no recollection of their

existence at that time. Dazzled by the lights, the noisy crowds, the

garish booths lining each side of the road, with the broad night sky

above, and, beneath me, my father's safe shoulders, I was unaware of

everything but my own bliss. Joyce used my 'ride' in a 'minor key' at

the very end of Finnegans Wake, when the approach of night was leading

him to seek again the warmest, surest haven he had known, that of his

own father, his 'mad-feary' father's unswerving love.

Today, with my eightieth birthday well behind me, other happy things well up to the surface....'

Maria Jolas A Woman of Action – A Memoir and Other Writings (2004) p 9

Richard Ellmann

claimed the line was 'inspired by a memory of carrying his son George

through a toy fair in Trieste to make up for not giving him a rocking

horse' - but gave no source for the story.

Adaline Glasheen, who was told the Jolas story by Hugh Kenner, provides the source of Ellmann's version:

'Dear Hugh my doesn't the world of Joycean fact slip like soap, slither like dreams. Maria Jolas says it was her toy-fair. Helen Joyce told me that Giorgio [Joyce] told her it was his toy-fair in Trieste, through which his father carried him.'

Adaline Glasheen to Hugh Kenner, 1 September 1977, Burns (ed), A Passion for Joyce: The Letters of Hugh Kenner and Adaline Glasheen, University College Dublin Press, 2008, p268

I like Maria Jolas's description of Joyce's feelings for his own father here too. Finnegans Wake can be read partly as a tribute to him. He's the main model for H.C.Earwicker who, in Joyce's earliest notes, was simply called 'Pop'.

| |

| Joyce's VI B 3 notebook, compiled in 1923 |

In 2008, when our online group first read this page, the late Karl Reisman commented:

Dominique (Cachou Le Pitou) answered:

'No Karl, not crazy, it's baby tuckoo, the moocow, and the Mississippi Hare coming for to carry us home.'

'If I seen him bearing down on me now under whitespread wings like he’d come from Arkangels, I sink I’d die down over his feet, humbly dumbly, only to washup.'

This is the most mysterious part of the ending. Anna's mind is disintegrating, and this feels like an hallucination in which father, husband, the white waves of the sea and an angel of death are jumbled together. Angels often appear in near-death experiences.

There's also the river water sinking under the sea ('I sink I'd die') and then washing up (also wake up and worship). 'Wash up' is US slang for ending something, says the OED quoting:

'The stage manager called out: ‘What will I do with this act, Mr. Ziegfeld?’ ‘Wash up him and the bird,’ said Flo [Ziegfeld] and that was the last of the Italian and his trained canary... Hype Igoe, the World's sporting writer, heard of the incident..and in commenting..upon Frank Moran, heavy weight pugilist, advised that matchmakers ‘wash him up’. The phrase caught the sporting fancy..and has become a colloquial fixture..as a meaty synonym for finals and farewell.'

The World, 25 October 1925

I wonder if Joyce knew that.

'I seen'

Arkhangelsk was the chief seaport of medieval Russia. Like Dublin, it lies on both banks of a river beside a sea. A local legend, shown on its coat of arms, claims that the Archangel Michael defeated the devil here.

|

| 'whitespread wings' |

Anna speaks as a working-class Dubliner, like the constable in Ulysses, who tells Corny Kellaher 'I seen that particular party last evening.' The 'him' and 'his' reminds me of Molly Bloom's monologue, where all men are simply 'he'.

I've found white wings and the sea in another poem of Swinburne:

'The keen white-winged north-easter

That stings and spurs thy sea'

'A Swimmer's Dream'

'White breast of the dim sea. The twining stresses, two by two. A hand plucking the harpstrings merging their twining chords. Wavewhite wedded words shimmering on the dim tide.'

Telemachus

'For I feel I could faint. Here weir, reach, island, bridge. There! That's what cockles the hearty! A bit beside the bush and then a walk along the

Paris,

1922—1938.'

'The keen white-winged north-easter

That stings and spurs thy sea'

'A Swimmer's Dream'

But there's also a sentimental song:

''White Wings" they never grow weary,

They carry me cheerily over the sea.

Night comes, I long for my dearie,

I'll spread out my "White Wings"

And sail home to thee.'

They carry me cheerily over the sea.

Night comes, I long for my dearie,

I'll spread out my "White Wings"

And sail home to thee.'

Maybe there's another echo of Yeats's 'who goes with Fergus?' sung by Stephen to his dying mother:

Telemachus

Any other ideas?

'We pass through grass behush the bush to.'

This part is left over from Joyce's first version of the ending:

Paris,

1922—1938.'

As in the published version the A and L of 'along' is completed by the P of 'Paris', giving us Anna's initials - matching the HCE of the book's opening. But it's interesting that Joyce, who had written the second part of the sentence twelve years earlier, did not then know how it would begin.

On the third typescript, he crossed that ending out and moved the 'pass through grass' phrase back to this position. He changed 'beside' to 'behush' continuing the rushing sounds of the sea and 'hush'.

'Here, weir...' was moved back to 626.97 but 'That's what cockles the hearty!' disappeared from the text.

'Far calls. Coming, far!'

Father calls and Anna answers, "I'm coming father!' These are also the calls of the gulls and a lighthouse (Phare in French). In our online group, Eric Rosenbloom commented, 'a word for sea in Irish is farraige, stress on 'farr'. It's a 'feminine' noun.'

'But soft! methinks I scent the morning air' Hamlet.

'But soft! What light through yonder window breaks?' Romeo and Juliet

'Far calls. Coming, far!'

Father calls and Anna answers, "I'm coming father!' These are also the calls of the gulls and a lighthouse (Phare in French). In our online group, Eric Rosenbloom commented, 'a word for sea in Irish is farraige, stress on 'farr'. It's a 'feminine' noun.'

The phrase is the title of one of Toru Takemitsu's lovely 'tonal sea' pieces. Thank you Steven Eric Scribner for sharing this on Facebook.

'End here. Us then. Finn, again! Take.'

Finn is Finn MacCool, HCE as the sleeping giant of Dublin. Finn is also Fin (end). These seven words recreate the final sentence's movement from ALP at the end to HCE (again!) on the opening page.

Joyce is giving us a clue to the book's title, still a secret when he wrote these words. 'Take' - it's an offering.

'Bussoftlhee'

But softly.

Soft again but now with Shakespearian meaning of 'wait' (or 'quiet' as in 'behush' above).

'But soft! What light through yonder window breaks?' Romeo and Juliet

'But soft! ' 462.25

'Adieu, soft adieu' 563.35

'Adieu, soft adieu' 563.35

A buss is a kiss, which shortly follows.

'mememormee!'

Remember me! and 'me me more me' - an attempt to hold on to her identity. Remembering and forgetting runs through the ending.

In his introduction to the Oxford paperback edition, 'mememormee' is the only word from the final page quoted by Finn Fordham, who describes the ending as a 'death aria'.

The word recalls Dido's lament ('when I am laid in earth') from Purcell's Dido and Aeneas:

'Remember me, remember me, but ah! forget my fate.

Remember me, but ah! forget my fate.'

Remember me, but ah! forget my fate.'

In Purcell's opera, the aria is followed by a chorus with more wings:

and scatter roses on her tomb,

soft and gentle as her heart;

Keep here your watch, and never part'

'till thousndsthee'

'in this scherzarade of one’s thousand one nightinesses' 51.04

'And into the river that had been a stream (for a thousand of tears had gone eon her and come on her...' 159.10

'We’ve heard it sinse sung thousandtimes.' 338.01

'one thousand and one other blessings will now concloose thoose epoostles' 617.04

'A hundred cares, a tithe of troubles and is there one who understands me? One in a thousand of years of the nights?' 627.14

'Lps. The keys to. Given!'

Some readers read this as a message from Joyce that he has given us the keys to reading Finnegans Wake.

J.S.Atherton explains the allusion in his brilliant Books at the Wake:

This is also mentioned in the lessons chapter, by Issy:

In the earlier version there's a clearer sense of keys as a reciprocal gift of love:

But the first sentence above was moved back to 626.30.

'I will give you the keys of my heart' is a line from 'The keys of heaven' ( which sounds like 'The keys to. Given!').

In The Sleeping Beauty, the heroine is awakened by a kiss, referred to a few pages earlier in Anna's letter:

THE FINAL SENTENCE

'A way a lone a lost a last a loved a long the'

This is what Joyce wrote, but Faber's typesetters managed to lose 'a lost'!

The last words were prefigured in 'The Dead':

'How pleasant it would be to walk out alone, first along by the river and then through the park!'

Joyce talked about that final 'the' with Louis Gillet:

'How pleasant it would be to walk out alone, first along by the river and then through the park!'

Joyce talked about that final 'the' with Louis Gillet:

'In Ulysses, to depict the babbling of a woman going to sleep, I had sought to end with the least forceful word I could possibly find. I had found the word 'yes', which is barely pronounced, which denotes acquiescence, self-abandon, relaxation, the end of all resistance. In Work in Progress, I've tried to do better if I could. This time, I have found the word which is most slippery, the least accented, the weakest word in English, a word which is not even a word, which is scarcely sounded between the teeth, a breath, a nothing, the article the.'

Louis Gillet, Stèle pour James Joyce, Marseille 1941, pp.164-65

For a whole essay on the final word, see Jim Le Blanc's 'The Closing Word of Finnegans Wake', in Hypermedia Joyce Studies.

But the last page doesn't end there.

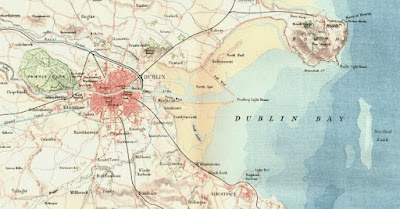

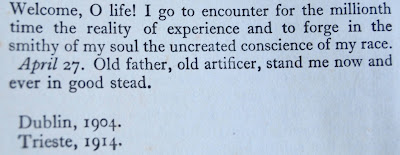

Joyce liked to end his novels with a colophon ('finishing touch' in Greek) giving places of composition. This is how A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man ends, with another invocation of a mythical father.

With Finnegans Wake, Joyce could have written 'a colophon of no fewer than seven hundred and thirty two strokes tailed by a leaping lasso' (123.05) for he wrote the book in Nice, Paris, Bognor Regis, Tours, Saint-Malo, Ostend, Antwerp, London, The Hague, Brussels, Amsterdam, Rouen, Zurich, Le Havre, Torquay, Llandudno, Hamburg, Copenhagen and several other places – see the list of his addresses in Danis Rose's Textual Diaries of James Joyce.

But he needed just 'Paris' for Anna Livia Plurabelle's inititals.

The date was '1922-1938' until January 1939, when Joyce changed the second date while correcting the galleys.

'WE CANNOT IMAGINE A FITTER SWAN SONG'

'The key of Ulysses is too bright, its movement too rapid for that pity and reconciliation which provide the magical end of the story, 'The Dead', to have any part in it, but that same human element expressed with yet greater artistry does return in the last pages of Finnegans Wake when Anna Livia goes forth by day, as a woman (wife and mother, representative of all flesh) to join the countless generations of the dead, as a river to become one with the god, her father Ocean....The last work of Joyce ends, as did his first, in the contemplation of the mystery of death. In both cases the rebellious pity of the human heart finds in the beauty of a constant element of nature — in the one falling snow, in the other smooth gliding water — the symbol and the instrument of reconciliation with human destiny. We had hoped for further years and other labours. We cannot imagine a fitter swan song.'

'Chapters of Going Forth by Day', James Joyce and the making of Ulysses, OUP, 1972, p 341-2

Paul Léon wrote that writing the ending for Joyce was a 'veritable deliverance':

'In Memory of Joyce', Poésie No V (1942), reprinted in James Joyce Volume 2: The Critical Heritage, (ed Robert Deming)

Eugene Jolas described the 'profound anguish' Joyce felt at writing this ending:

'For Joyce himself, Finnegans Wake had prophetic significance. Finn MacCool, the Finnish-Norwegian-Irish hero of the tale, seemed to him to be coming alive again after the publication of the book, and in a letter from France I received from him last spring, he said: '...It is strange, however, that after publication of my book, Finland came into the foreground suddenly'....'Prophetic too, were the last pages of my book,...'he added in the same letter. The last pages, that had cost him such profound anguish at the time of their writing. 'I felt so completely exhausted,' he told me when it was done, 'as if all the blood had run out of my brain. I sat for a long while on a street bench, unable to move....'

'And it’s old and old it’s sad and old it’s sad and weary I go back to you, my cold father, my cold mad father, my cold mad feary father, till the near sight of the mere size of him, the moyles and moyles of it, moananoaning, makes me seasilt saltsick and I rush, my only, into your arms.'

There was no turning back after these lines, my friend. You knew it well. Adew!'

Eugene Jolas, 'My Friend James Joyce', Sean Givens (ed) James Joyce: Two Decades of Criticism, Vanguard Press, 1948, p17-18

'And it’s old and old it’s sad and old it’s sad and weary I go back to you, my cold father, my cold mad father, my cold mad feary father, till the near sight of the mere size of him, the moyles and moyles of it, moananoaning, makes me seasilt saltsick and I rush, my only, into your arms.'

There was no turning back after these lines, my friend. You knew it well. Adew!'

Eugene Jolas, 'My Friend James Joyce', Sean Givens (ed) James Joyce: Two Decades of Criticism, Vanguard Press, 1948, p17-18

To Constantine Curran, 11 February 1940, Letters, p 408

Did Joyce mean that he believed he was prophesying the death of European civilization? Or did he imagine that his own life was coming to an end?

'when the approach of night was leading him to seek again the warmest, surest haven he had known'

Maria Jolas

For the rest of the 'suspended sentence' (106.13) which continues on the opening page, see my post, 'The sentence it took Joyce twelve years to write'.